Stress and pressure are part of daily life. The modern world seems to have sped up and we are often expected to juggle multiple priorities at once. This can cause difficulties for some people but there also seem to be people who are really good at managing the stress or significant pressure in their lives. If we learn from this second group, everyone can perhaps better manage the pressure upon them more wisely.

Consider some of the following statistics gathered from a number of research projects:

- 80% of people reported that their work was very stressful;

- 50% viewed their work as the number one stressor in their lives;

- 80% of people believe that they have more on-the-job stress than a generation ago;

- 40% of people felt a lot of stress at work;

Even though stress is a big issue today not all stress is bad, and learning how to deal with and manage it in a balanced way is critical to maximising our outcomes, staying safe, and maintaining our physical and mental health. Infrequent exposure to some “gentle” stress poses minimal threat and may actually be quite effective in increasing motivation and output. Too much stress and prolonged exposure to pressure however can lead to a downward spiral.

In general, stress or pressure can arise from two sources:

- Pressure that life can put on us from time to time, and

- Pressure that we put upon ourselves as we react to different situations

Toleration of stress and pressure tends to vary from one person to the next, largely because people cope with it quite differently. Most people typically feel very little in the way of pressure when they have the time, ability and resources to manage a situation or event. However, most of us experience significant pressure when we think we can’t handle the demands put upon us. In this way, stress can be a very negative experience, but it is not necessarily an inevitable consequence – it depends on your perception and your ability to manage it adequately.

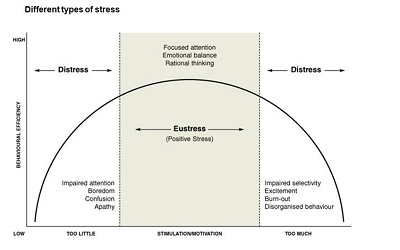

Some pressure can provide healthy stimulation and help us feel motivated and energised to get things done. However, too much pressure can lead to anxiety and unhealthy personality changes. In other words, if you draw stress as a normal “bell-shaped” distribution curve, there is a healthy segment in the middle of the curve and unhealthy segments at the two ends of the curve – too little pressure and too much pressure can both be problematic. Let’s therefore briefly describe the three types of stress on this curve:

Eustress

In the middle part of the curve, called eustress, is optimal pressure or stress that provides a degree of immediate energy and motivation to act. Eustress often arises at points of increased physical activity (think of an “athlete’s high”), enthusiasm, and creativity. Eustress is positive stress that arises when motivation is high and we feel able to handle difficult or complex tasks or a lot of pressure at once. We all have the capacity to be in the eustress zone a lot of the time with good pressure management skills operating consistently.

Distress

At the low stress end of the curve is distress. Distress is a negative stress state, typically brought about by too little happening around us and often leading to apathy, confusion or tiredness. Distress creates feelings of discomfort and boredom. Distress may last for a few hours or can be a prolonged stress that can exist for weeks, months, or even years.

Hyper-stress

At the high stress end of the curve is Hyper-stress. Hyper-stress occurs when an individual is pushed beyond what he or she can handle. Hyper-stress results from being overloaded or overworked. When someone is hyper-stressed, even little things can trigger a strong emotional response. Prolonged states of hyper-stress can often overwork the immune system and lead to serious illness.

Managing your stress

If you are experiencing “distress”, or too little stress or pressure, you might want to try to push yourself into the eustress part of the stress curve by looking for additional challenges, finding more to do, or changing what you do to increase the stress to a more optimal level for you. Boredom can result when you are not taking enough initiative, or are not sufficiently challenged. If you are experiencing hyper-stress, on the other hand, you might want to try to take things a little more slowly, delegate things where you can and find ways to relax or take a break. This is not always easy but it helps to avoid feelings of chronic fatigue or illness if you do nothing.

In summary, the more we can recognise when we are in each of these three types of stress situations, the better able we will be to manage ourselves and our reactions and maintain a healthy balance of pressure in our lives.

Related Resources:

Psychological Type and Stress Management: Training Handout (PDF)

Managing Change: Coaching Guide with Storyboard – Ministry Specific Resource (PDF)

Managing Change Storyboard – Ministry Specific Resource (PDF)

Comment here